Knights of the Free State of Nickajack

The First Alabama Cavalry, United States Volunteers

By Steve Ross

In war it’s helpful if soldiers learn to hate the enemy, something the citizens of a democracy aren’t normally brought up to do. In the case of the 1st Alabama Cavalry, United States Volunteers, however, hatred for their enemy wasn’t something learned under fire. Soldiers of the regiment brought their hatred for secession, and secessionists with them to the battlefield. Their blue uniforms clothed a red fury at the state government and its citizens that sought to coerce them into the Confederate army. These minions harassed and brutalized their families, drove them from their homes into the Alabama hills, then into Union lines, and at last into the ranks of the U.S. Army.

In an irony not lost on modern historians, the Confederacy, created to preserve the principle of states’ rights over the primacy of the central government, instituted the first wartime draft in American history. Passed by the Confederate Congress in April 1862, it imposed manpower quotas on the individual states. Every able-bodied white male between the ages of 18 and 35 was subject to military service. Each state was required to produce a certain number of men for the Confederate armies. If a state’s quota wasn’t filled by volunteers, the men must be conscripted. In the hill counties of the Southern states, including north Alabama, volunteering fell far short of the numbers required. Frustrated at the refusal of these “tories” to see the light, Governor Frank Shorter of Alabama sent conscription parties, most composed of Home Guards, into the northern counties with leave and license to coerce their reluctant neighbors into the Confederate army. To refuse meant jail at the very least, and, quite possibly, death. To make matters worse, through much of the war north Alabama was occupied by the forces of both sides, and groups of bushwhackers, many of them deserters from both armies, sprang up to prey on the people. Farms were burned, livestock, goods and money looted, and murder was not uncommon. Little wonder, then, that these men, set upon in every conceivable way by their fellow citizens, chose to take up arms and return the favor.

In an irony not lost on modern historians, the Confederacy, created to preserve the principle of states’ rights over the primacy of the central government, instituted the first wartime draft in American history. Passed by the Confederate Congress in April 1862, it imposed manpower quotas on the individual states. Every able-bodied white male between the ages of 18 and 35 was subject to military service. Each state was required to produce a certain number of men for the Confederate armies. If a state’s quota wasn’t filled by volunteers, the men must be conscripted. In the hill counties of the Southern states, including north Alabama, volunteering fell far short of the numbers required. Frustrated at the refusal of these “tories” to see the light, Governor Frank Shorter of Alabama sent conscription parties, most composed of Home Guards, into the northern counties with leave and license to coerce their reluctant neighbors into the Confederate army. To refuse meant jail at the very least, and, quite possibly, death. To make matters worse, through much of the war north Alabama was occupied by the forces of both sides, and groups of bushwhackers, many of them deserters from both armies, sprang up to prey on the people. Farms were burned, livestock, goods and money looted, and murder was not uncommon. Little wonder, then, that these men, set upon in every conceivable way by their fellow citizens, chose to take up arms and return the favor.

Slowly, by ones, twos, and handfuls, the north Alabama men filtered into the Union lines around Corinth, Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee. By the middle of 1862, Union forces also occupied Decatur, Huntsville, and Nashville.

Although generally unknown today, all eleven states of the old Confederacy, including Alabama, had expatriate sons who fought in Union blue. Strong ties to the “Old Flag” existed in the South, mostly in the hill country where few owned slaves. They had no wish to fight what they saw as a planters’ war to preserve slavery and the political and economic power that went with it.

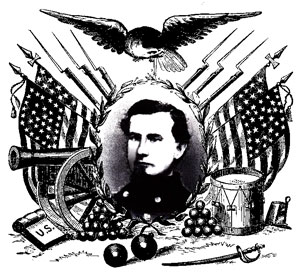

Unionist feeling in Alabama was strongest in the northern half of the state and, while centered in Winston County, was heavy throughout the region. The 1st Alabama Cavalry, U.S. Volunteers was the military result of that anti-secession feeling. The regiment was formed in October 1862 in Huntsville and Memphis, and mustered into Federal service that December in Corinth, Mississippi. Company officers were chosen from among the men and Captain George E. Spencer was later named Colonel and given overall command. The “1st” was one of six Union regiments from Alabama, the only cavalry unit, and its ranks contained both whites and blacks. The other five were infantry and artillery units raised during the war, were composed of ex-slaves, and officially called “African Descent” regiments.

During the war over two thousand loyal Southerners served in the 1st Alabama: farmers, mechanics, traders and others, from 35 counties of Alabama and eight other Confederate states. They ranged in age from as young as 15 years to as old as 60. Some, young and old, lied about their ages in order to enlist. The 1st Alabama mustered men from 35 Alabama counties, and eight other Confederate states. There were also men from the border states of Kentucky and Missouri, from seven northern states, and from eight foreign countries. The “1st” WAS diversity 130 years before it became “politically correct.”

During most of its operational life, the 1st Alabama was part of the 16th Corps, Union Army of the Tennessee. In its early months, the unit filled traditional cavalry roles of the time; scouting, raiding, reconnaissance, flank guard and screening the army on the march. The regiment fought mostly in actions associated with those missions: actions no less deadly for being small. It’s not known if the regiment had a battle flag. None has ever been located, nor can mention be found in memoirs of the original troopers. Experts at the Alabama Department of Archives & History point out that battle flags were generally given to departing units by the states that raised them, or the communities in which they were recruited. These experts suggest that since the 1st was in a sense an |

Colonel George E. Spencer |

| “orphan” unit, it had no regimental flag of its own. Whatever guidons or banners it may have carried were very likely standard U.S. issue from stores on hand. But if the 1st Alabama ever had a regimental flag, it would have carried names such as Nickajack Creek, Vincent’s Crossroads, Cherokee Station, Monroe’s Crossroads and others, hardly known at the time and all but forgotten today. There are better known places too, such as Streight’s Raid through north Alabama; and battles at Dalton, Resaca and Kennesaw Mountain in the Atlanta campaign. Men of the 1st fought and fell on many fields in their country’s service. |

By the time Sherman’s forces entered Atlanta in late 1864, the “1st’s” reputation was secure. One general called the Alabama troops “invaluable...equal in zeal to anything we discovered in Tennessee.” And Major General John Logan, commanding the 15th Army Corps in Sherman’s forces, praised the troopers as “the best scouts I ever saw, and (they) know the country well from here to Montgomery.” General Sherman, knowing the value of his Alabama troops as soldiers and symbols of the loyal South, chose them as his escort on the march from Atlanta to the sea.

The honor of guarding the Army’s commander, however, did not keep the 1st Alabama Cavalry from the line of fire. On 10 March 1865, soon after entering North Carolina, the 1st was embroiled in its hardest fight. At Monroe’s Crossroads the regiment was surprised in its camp by the dawn attack of Confederate cavalry under Generals Joseph Wheeler and Wade Hampton. The official report said that “a bloody hand-to-hand conflict” followed, lasting more than three hours. Only the timely appearance of a section of field artillery enabled the hard-pressed Alabamians to drive the Confederates from their camp and hold them off until help came.

Judson

"Kill Cavalry"

Kilpatrick |

When the smoke cleared, the Third Brigade of Judson Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry division, including the 1st and two other regiments, about 800 men, had routed 5,000 Confederates. The rebels lost 103 dead and many more wounded at a cost to the Federals of 18 dead, 70 wounded and 105 missing. A potential disaster had become a clear cut victory. A few weeks later, the 1st was present at the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate army and “Sherman’s March” was at last complete.

When the 1st Alabama Cavalry (U.S.V.) mustered out for good on 20 October 1865 only 397 men remained with the colors. In three years’ service the regiment lost 345 men killed in action, died in prison, of disease or other non-battle causes; 88 became POWs and 279 deserted. There is no accurate count of wounded. Bitterness between secessionists and loyalists in Alabama remained after the war. It soured state politics for over a century and traces of it can still be seen. Many old troopers suffered for their loyalty, legally, politically and socially. But they’re remembered, and honored, by their descendants today. |